Coffee Shops, Third Places and Social Design

How we exist together in our third (and fourth...) places

It feels a bit meta to write about coffee shop culture from a coffee shop, but it also makes it feel even more worth thinking about. While I am currently writing this from a café in north west London, a few months ago I was working from the coffee shops of China and Indonesia, as I mentioned in my last post. In China in particular, I was reminded of how different the coffee shop culture is there, compared to my experiences in London and in parts of western Europe and the US, which struck me on my first visit in 2024 and my return this year.

I particularly remember a coffee shop I went to that is part of my friend’s apartment building in Shenzhen, in southern China. You take off your shoes at the door and put on a pair of sliders, or covers over your outside shoes. You then step into a space that has been made to feel more like someone’s living room than a café. There’s a bunch of cosy sofas and arm chairs, book shelves and a big TV screen showing a nature documentary. I personally sat on a couch eating a strawberry croissant and watched a documentary about volcanos for an hour. Coffee shops in China tend to be far more elaborate and interesting than those I have encountered in London, at least from my foreigner’s perspective, from more exciting drinks (e.g. osmanthus latte or grapefruit espresso) on menu to themed decor.

My ‘local’ coffee shop in Shenzhen, southern China (credit to my friend Hannah for finding this image for me on DianPing)

The high concept design of Chinese cafés can be tied to their greater role as ‘third spaces’, as many young people in large Chinese cities like Shenzhen have small apartments and need a space to exist outside of work and home. The term ‘third space’ itself has become increasingly mainstream around the world, as cultural commentators and ordinary citizens alike try to pinpoint the precise causes of social isolation and loneliness crises in a range of countries. The concept of a ‘third space’ originates from Ray Oldenburg’s The Great Good Place, where he discussed the idea of the third place, a place that is neither work nor home, marked by qualities like inclusivity, neutrality and a ‘levelling effect’ amongst people. The difference of Oldenburg terming it a ‘third place’, not a ‘third space’, is key because it makes place-making a crucial component for forging social connection. In the formal ‘place making’ urban planning approach, people are empowered through consultations and community-led design workshops to transform spaces into places that reflect their cultural values and needs. It’s the associations and significance that people give to a space that make it a place.

Our dominant cultural conversation around third spaces seems to indicate that the issue is we just don’t have enough spaces, so ‘if you build it’ (a space outside of work and home where people can spend extended periods of time for leisure), ‘they will come’ (people who will build community together). This is a real concern - free, state-funded spaces in particular, like libraries and youth clubs, are being cut or consolidated, at least in the UK. However, this focus on the scarcity of space neglects the importance of how people are encouraged to interact in order to make a space a place with meaning and value. I will be using the terminology of ‘third space’ and ‘third place’ interchangeably throughout this article, because this is how they show up in the literature and media I have consumed. However, ‘third place’ is still the ideal term for me, as it takes into greater account the role we play as participants to give somewhere social significance. I want to examine how our behaviour in relation to these places is shaped by the design of a space and the assumptions governing that design, but also external cultural norms that shape how we exist together in and beyond that space.

In the process of research for this article, I visited the National Art Library, housed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, a good third place in itself. Amongst many other texts available, I found books detailing the evolving design of cafes and coffee shops across time and space. I looked at coffee table books cataloguing early 2000s cafe design like Cafes and Coffee Shops No.2 (2001) by Martin Pegler and Bars, Pubs and Cafes: Hot Designs for Cool Spaces (2002) by Julie D. Taylor, as well as the more up-to-date BRANDLife: Cafes and Coffeehouses (2016) from Viction Workshop. The difference between the 2000s and 2010s era coffee shop design was stark. The cafes featured by Pegler and Taylor had far more soft furnishings, warmer tones and primary colours. However, the most crucial element is that these cafes and coffee shops had much more variation in design, as well as integration of high concept or themed decor. This included a fair bit of cultural appropriation, such as Riki Tiki Tavi cafe in Manchester (throwback to the Tiki analysis of my last article) and the Caribbean-themed Naked Fish in Boston. However, there was a sense of creativity and imagination in the over-the-top decor and themes that feels lacking in the current coffee shop landscape, at least in the UK.

A photo of Riki Tiki Tavi, from Cafes and Coffee Shops No.2 (2001)

These books reminded me of one of my favourite niche aesthetics - the global village coffeehouse aesthetic. This aesthetic style originated in the late 80s and continued to develop until the late 90s / early 2000s, with the name referencing the ‘global village’ concept of the early internet and the frequent representation of coffeehouses in its imagery. The aesthetic has a hand-drawn and textured style, and features motifs like the globe, aroma swirls and simplified human figures. Think early Microsoft Clip Art, crossed with ‘end of history’ optimism. The frequent inclusion of coffeehouses in the aesthetic - so much so they are in the name - reflects the place they took up in the cultural imagination, or at least in the US corporate milieu the aesthetic originated from. The coffee shops represented epitomised a bohemian sensibility tied to cafe culture of old with the naive embrace of globalisation and (at least superficially) multiculturalism of the turn of the century.

Examples of the global village coffeehouse aesthetic, from this article by Vox

By the time you get to the 2010s, the aesthetic of coffee shops evidenced in BRANDLife: Cafes and Coffeehouses has become a lot more uniform. It’s minimalist, it’s white and charcoal grey, it’s exposed brick and pale wood, it’s visible pipes and industrial light fixtures. Of course, there were some stand-outs in the book that bucked the trend. One of my favourites was the Pantone cafe in Monaco, where every product is colour coded and labelled to reflect Pantone’s original colour identification system. I also loved the example of Le Batinse in Quebec City, inspired by ‘grandma’ cuisine and decor, with crochet lampshades and floral curtains. However, the general shift was to a much more homogenised, stripped back aesthetic. This can be mapped onto the ‘third wave’ of coffee, which focused on more specialist coffee sourcing, roasting and brewing. The ideal of the high end coffee shop became much more focused on mimicking the efficiency and minimalism of artisanal production, to signal the quality of the coffee being produced.

A classic coffee shop case study from BRANDLife: Cafes and Coffeehouses

This trend also coincided with shifts in working patterns, starting in the 2010s and intensifying in the 2020s, and the emergence of a ‘laptop class’ of flexible and freelance workers and students. The coffee shop was turned into a quasi-workspace, at least during weekdays, transforming the quintessential third place into a proxy for the ‘second place’ (the workspace or office). This isn’t to say that the ‘second wave’ coffee shop of the 90s and 2000s in the Western world, characterised by big chains and blends over single origin, did not involve work-based activity at all. However, I would argue what I would term ‘the neoliberal coffeeshop’ phenomenon - of people using the coffee shop more often as a space for solitary work or scheduled meetings than for casual social interaction - was not as prevalent as it is now. Of course, a significant factor was that the technology was not available to work from coffee shops, to produce this atomised way of being in the first place. However, the broader push for individualism and self-optimisation in contributing to this compartmentalisation - one frequently attributed to the current ‘loneliness epidemic’ - cannot be overlooked either.

Again, I am very much participating in this phenomenon at this very moment, writing this in a coffee shop surrounded by other people working on laptops. But I always wonder if things could be different, or if we can imagine an alternative. Coffee shops have been valued across time and space as spaces for gathering and fostering social connections, and with that often the development of new ideas and political activism. Early coffeehouses in London in the 17th and 18th centuries functioned as public social spaces - albeit largely for men - to discuss current affairs and political debates. It has been argued that the absence of alcohol facilitated more serious discussion, compared to the other notable British third place of the time, the ‘pub’ (or public house).

The earliest known image of a London coffeehouse, from 1674. Found from this article in Public Domain Review and sourced from William Harrison Ukers’ All About Coffee (1922).

With this absence of alcohol in mind, cafés and coffeehouses have also played a significant role in social and political developments in many Muslim countries - in fact, coffee making is argued to originate in the Islamic world. Through a short form video from creator @sincerelytahiry, I learnt about the history of coffee brewing in Yemen by Sufis from around 1400 CE and the significance of coffee in sustaining late night collective worship. Tahirah examines how this laid the ground for criticism from political and religious authorities in 15th century Yemen, both of coffee itself as potential khamr or intoxicant (equivalent to alcohol) and from the fear of coffee houses as a place for sedition and rebellion. She then links this to contemporary criticism of young US Muslims using Yemeni coffee shops as a third space, with some concerned about the risks of ‘free mixing’ (unconstrained interaction between men and women) in these spaces. Tahirah details her sources for the above video in this Substack post, which includes another mini video essay from @rozanawithrida that similarly looks at the role of coffee houses in the Indian subcontinent in political organising and intellectual life in the region.

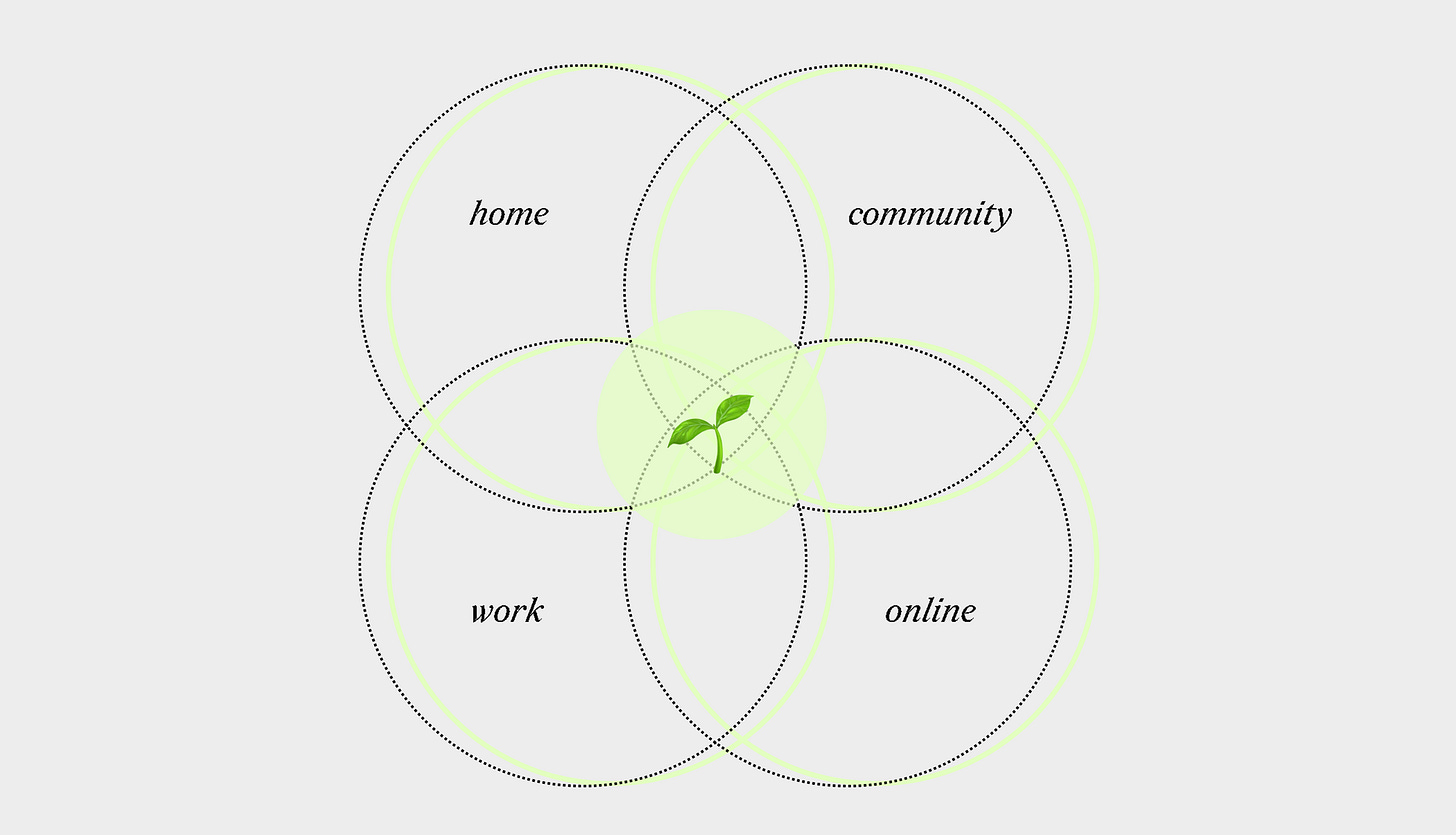

Of course, the ability for coffee houses to function as crucial spaces for social connection and political organising across these times in history was shaped by the fact that there were limited means in which to do so otherwise. In a time where we are more technologically connected, what is the role of the coffee shop and of third places in general? This recognition has led some to argue that we need a new framework to discuss the function that public space is playing today - no longer a third space, but a fourth space. I came across this term initially from an article on Fourth Spaces sparked by a contribution from Mariella Agapiou for Protein’s SEED Club - which also published my article on Medieval Nostalgia here. She found the initial concept from Eventbrite’s Fourth Spaces report this year, which defines fourth spaces as “gathering places that transcend physical location, bringing people together through shared passions and bridging online communities with real-world connections.” Essentially, fourth spaces are the next development in the first / second / third place theory, where home, work, community and the online world can all intersect in settings that are intentionally curated.

A venn diagram outlining the intersections of Fourth Spaces from Mariella’s article

While this was a new idea to me, Mariella identifies that this has existed in anthropological literature for a while, referencing an article from anthropologist Giulia Balestra on the fourth place. In my own research, I found a book chapter from Jan Rath and Witze Gelmers from 2016 on ‘Trendy coffee shops and urban sociability’, that also references the idea of the fourth place. Rath and Gelmers write about the shifting place of coffee shops, observing in their ethnography in Amsterdam that Ray Oldenburg’s ideas about the third place were not completely applicable. People are more likely to be interacting either with fixed groups with people and social networks not physically present via digital technologies. This creates “a complex duality of social interaction, one that alternates between the actual and virtual domains”. This leads them to argue, “Now that online interaction has become an undeniable part of human behaviour in urban public spaces, our conceptualisation of ‘social interaction’ and ‘social atmosphere’ may need to be revised.” Therefore, “one could speak of a fourth place, even if that raises questions about the word ‘place’ when referring to interactions that occur in virtual, abstract domains” - i.e. the fourth place challenges conventional definitions of what a ‘place’ even is in a digital age.

They also observe that the practice of ‘civil inattention’ - freely existing in a public space without others noticing (or being aware of them noticing) or interfering with you - is a fundamental quality of social interactions of specialty coffee shops. These new rules of social interaction push them in the new category of ‘fourth place’. This ties into an argument from Paul Robbins in his paper on ‘Rethinking public space: a new lexicon for design’. He argues that the designation of ‘public space’ has become increasingly ambiguous and unclear as our scripts of encounter and co-existence have been forced to change. Robbins reflects on patterns of exclusivity and accessibility in how space is used, with privately owned spaces often being more accessible and more inviting than those officially framed as public, making the public / private opposition more blurred and less analytically helpful. He also analyses how public space has become a space more of uncertainty and tension, as strangers come with drastically different understandings of how to behave into public space, yet still assume themselves as part of a collectivity. As a result of the uncertainty of the public spaces, he argues that people flee this social risk and seek out ‘private’ spaces like malls or cafes, because increasingly “We find more social solace and security in the private than the public.”

Taking on this awareness that the expectations of ‘third places’ may no longer be applicable and our understanding of public spaces needs to change, how do coffee shops and other places outside of home and work shift in relation to this? I have been interested in the approach of social design for a while, which is defined as design for and with society. It aims to offer a more socially conscious perspective than traditional design thinking, by seeking to understand and address social issues within design choices. In an exhibition book I found titled Social Design: Participation and Empowerment, from Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, it detailed examples of innovative social design projects around the world. They inspired me to imagine better third places, even if they didn’t specifically design for coffee shops and cafés.

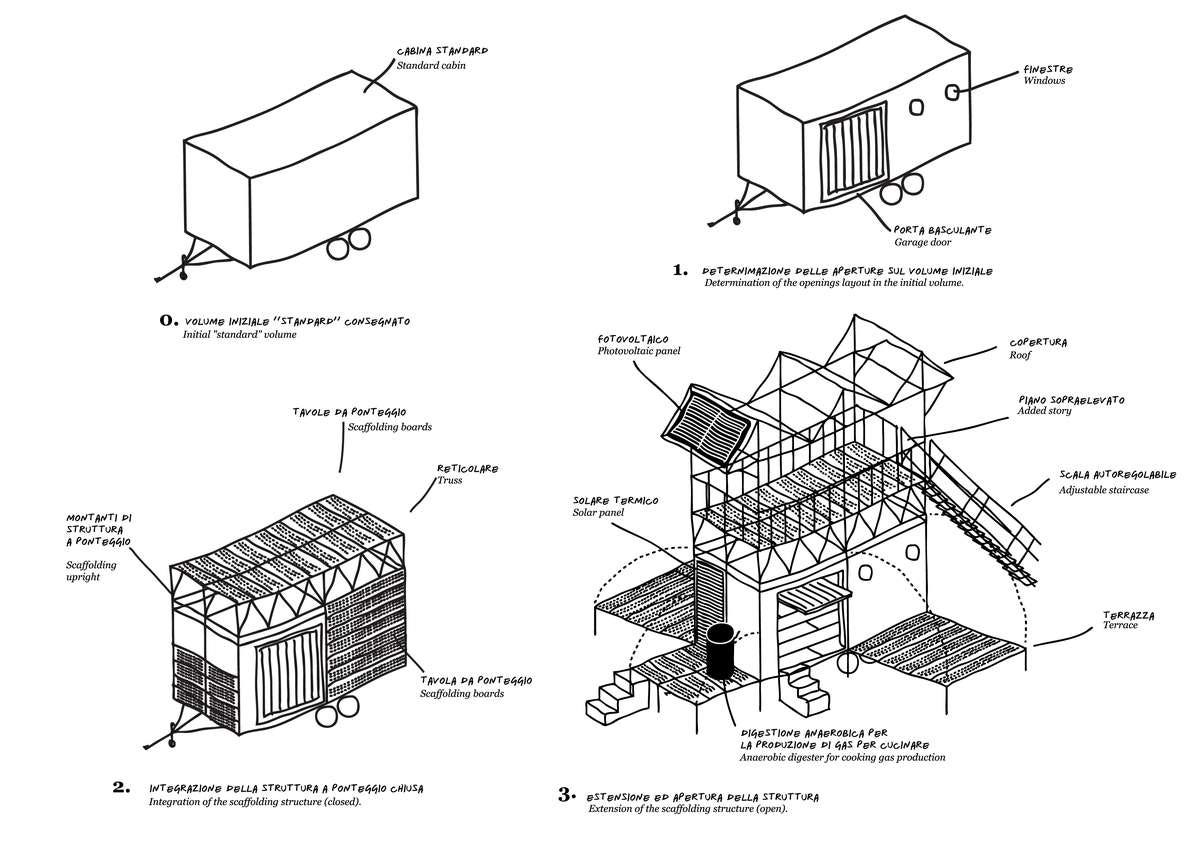

One that stuck with me was the Campo Libero (The Innocent House) by Antonio Scarponi. The Campo Libera was designed for the Italian organisation Libera, which works to reactivate land confiscated by the mafia in the south of Italy, and was showcased as a concept at the Venice Biennale. It is a mobile, self-sufficient and reversible pavilion that was conceptualised as a device to support the cooperative forms that Libera aims to establish to reinstitute a legal and equitable economic system in the region through cooperative farms. The stand-out feature for me was the Sedia Libera, a chair designed specifically for the pavilion, which emphasises the ‘right to sit’, and looks out on rural landscapes from the pavilion. By promoting this restful sitting, it ties into the Campo Libero’s design to be a platform for appreciation and reinvestment in the value of the southern countryside. The chair itself would be locally produced, with the possibility of outsourcing manufacturing to refugees who come to the region.

Plans for the Campo Libero pavilion, featured in Future Architecture

By designing the seating so intentionally to reflect the values of the space, it made me think about what the typical seating in specialty coffee shops says about the values of those spaces. Thinking about the booths and couches of the cafes I saw in the 2000s reference books I flipped through, vs. the hard wooden benches and chairs of many minimalist third wave coffee shops, what kinds of behaviour do they incentivise? How can we design these spaces that increasingly make up our public sphere to encourage rest and mindful appreciation, more so than the workplace values of productivity and efficiency? It reminded me of a piece I read by Jaishika Nautiyal about affect theory and coffee shops, which argues for coffee spaces as places of contemplative leisure that can enable rich aesthetic experiences. By viewing coffee shops as ‘everyday works of art’ that thrive on communicative rituals and centring habits, Nautiyal believes that they are spaces that enable personal growth and embodiment. From a philosophical perspective too, this makes designing spaces to facilitate these seemingly abstract values of thoughtfulness and leisure a more meaningful task than it might initially appear.

I love the possibilities offered by social design approaches, to imagine better alternatives for third and fourth spaces. At the same time, I recognise that even the most intelligent design in the world has to work in partnership with the values and belief systems of its users. To return to my initial thesis: to turn a third space into a place, and therefore get the social connection we want out of them, we need to look at the role we play as participants to give somewhere value and significance. We need to look at our willingness to take social risks, to prioritise connection over productivity, to invest in spaces that match our values. These are all issues that go beyond the scope of this essay to analyse in the depth they deserve.

However, using coffee shops as a framework to diagnose these social issues, we can hopefully understand both the potentials and limits to transform these roots of disconnection through our built environments. I will continue to take the small joy of finding a third place that breaks the mold and makes simply existing there a pleasure. In the small moments of being surrounded by other human beings - even if we are locked in with our respective noise cancelling headphones - I feel more connected to lives beyond my own.